The Emerging church should meet Scott Young. Why? He was practicing emergence before the words “emergent” and “emerging” became part of the public discussion about the church. He’s “premergent,” or perhaps “protomergent.” I met Scott when I was a student at a conservative Evangelical university in Southern California. I took his “Film and Society” and “Religion and Society” classes. He challenged our basic assumptions about Christianity and played the role of the provocateur in the classroom.

In addition to having taught at my school, along with Fuller Seminary, and Art Center: College of Design, Scott founded the City of the Angels Film Festival in 1994 and co-directed it until 2005. Scott’s been deconstructing the spiritual/secular binary for a while now. And for the last 30 years, Scott has worked as a campus minister with a well-known Evangelical organization. I found it helpful to hear him talk about living and working in these kinds of communities and not always “fitting in” theologically, ideologically, etc., especially as I negotiate my life as a post-Evangelical in my own Evangelical church community.

I got together with Scott to talk about some of these things in May of last year (2009.)

Scott Kushigemachi: It occurs to me that for a long time you’ve been wrestling with questions that have been taken up by many in the Emerging church movement—the appropriation of continental postmodern philosophy, the deconstruction of certain ecclesiological and theological structures, the suspicion of Foundationalism. Could you give a broad overview of the shape of your theological/spiritual journey, starting as a student at a conservative Evangelical college, up to the point where you are today?

Scott Young: When I was in college, I started a lifetime of questioning and engaged in what Paul Ricoeur called the hermeneutics of suspicion or Derrida’s sense of deconstruction. For me it was that my inherited faith structure didn’t make a lot of sense. The basic foundational pieces that I had been told were indispensable for a life of truth and goodness didn’t seem so essential. There was a shaking of the foundations, to use Paul Tillich’s term. Probably the most important thing that happened while I was an undergrad was I had a protracted period of doubt that was both spiritual, intellectual, and emotional. It was not an experience for which there was a lot of hospitality, or even tolerance, in that place, so it was very privately experienced, but it drove me to the library, and I started ransacking the library for books. There, I discovered two Christian thinkers who helped me reconnect a sense of intellectual curiosity and vitality with a Christian commitment.

In fact, one of the books was called Christian Commitment, by E.J. Carnell, and it was Carnell’s first attempt at reflecting on an experience he had encountering Søren Kierkegaard. I also ran into a book called A Place to Stand by the Quaker philosopher Eldon Trueblood, which was really an attack on Foundationalism without using that terminology.

After my undergraduate education, I attended seminary, which for me was not a time for career training, but an opportunity to continue to explore these questions that I was plagued with. In seminary, what I was really interested in was theology and culture, including philosophical questions and motifs, but also including the arts and things like street life and pop culture. Also, having come from a semi-rural area, I was really intrigued by the city, and so while going to seminary in Denver, I became a student and enthusiast of the city.

SK: In describing your life, you draw from Derrida and Ricoeur to help explain your autobiography as though these ideas “fit” the narrative of your lived experience. How did postmodern or poststructuralist ideas and theologies influence you?

SY: When I had a serendipitous discovery of Eldon Trueblood and E.J. Carnell, that set a pattern for me for looking for thinkers. That sent me into a discovery mode that continues to this day, where I consider myself—well it’s in the name of my blog: “culture vulture report.” I’m a scavenger, and I’m always looking for good ideas, and I have this primal curiosity that isn’t clustered but scattered: it goes in so many different directions.

Having been introduced to Kierkegaard, I later discovered all of Kierkegaard’s friends. And then there’s another layer after that, which is all of Kierkegaard’s commentators, and then Kierkegaard’s critics. And tracking that for over 40 years basically introduces you to the entire thought world, to all kinds of boulevards of ideas, and…I like traveling down boulevards.

I’m motoring down those intellectual boulevards, often taking joy rides, and sometimes I get out and window shop, and sometimes I hang out for a while and stop at a park along the boulevard. If you think of intellectual life as a kind of roadtrip, I’m both a flaneur, an observer and a watcher, as well as a participant—I walk the sidewalks, I get up close and personal. Discovery of salient thoughts requires both distance and proximity.

SK: If you had to identify where you’re stopping right now, who are you window shopping or hanging out with on that boulevard?

SY: To switch up the metaphors, let’s say I went into a theater for this one. So I’m looking at a stage, and in this play the marquee level actors would be John Caputo interpreting Derrida and Kierkegaard. Then there would be Rene Girard. And then there would be Mikhail Bakhtin. I’m currently enthralled watching this play in which they are performing the theatrics of thinking.

Paul Ricoeur I already mentioned. Gianni Vattimo. Then there’s Zizek, who’s an intellectual celebrity. I would have to include Cornel West. It’s a crowded theater—it’s more than three acts, so it’s kind of crowded up there. But those are some of the key figures. This gives new meaning to the theater of the absurd.

On the theological side, the powerful influences for me that anticipated this move towards deconstruction or postmodernism, or emergent, or whatever term you want to use, were Paul Tillich, both of the Niehbur brothers, and Harvey Cox.

In addition to that, among the liberation thinkers that really influenced me would be Kosuke Koyama, a Japanese liberation missiologist. Also, Dorothy Sölle, and I would have to add Gustavo Gutierrez.

SK: Another theme you’ve mentioned is the city. I know that your love of the city is connected to a sense of social justice. How did that aspect of your faith emerge? What prodded you in that direction? The intellectual curiosities and philosophical questions don’t necessarily lead a person in that direction.

SY: So how did this develop for me? During orientation week at college in September of 1969, I became the tour guide for a lot of people I met at orientation week who were from the Midwest and had never been to LA. So I ended up giving tours into the Hollywood Hills, Bel Air, Beverly Hills, but also I would take them to Olvera Street in downtown LA, which is the symbolic starting point, 250 years ago, of the city.

Olvera Steet is center city, so there was a large population of Skid Row panhandlers, the homeless variety of street people. They’re still there, but they’re more hidden now. At any rate, I just had a natural compassion—I’m not sure where that came from. And I went back to the staff person that was in charge of the “Christian service assignments” at my school and told him I wanted to start a ministry to Skid Row people on Olvera Street. And I can’t believe he said “Go ahead.”

But what I discovered was that there was something needed beyond mere personal charity. One story to illustrate it: I ran into a former boxer who was obviously an alcoholic. I promised that I would help him, and I was going to take him down the street to a hamburger joint to get him something to eat. As I was helping him in his drunken stupor across the street…what the LAPD used to do back then was they would drive up in these big patty wagons and they would literally just throw homeless people, and especially people who were intoxicated, they’d just throw them into the back of a truck, almost like piling trash. And here I had just promised this guy that wouldn’t happen. This was my first experience with the LAPD—it was a very negative one. I realized that personal compassion, caring, acts of charity, thousand points of light—that’s one piece of it…that’s not enough. I understood that there was something really wrong with the system.

SK: Since you became more conscious of the systemic and structural dynamics of social problems, how did you find ways to act upon that?

SY: My real activist life didn’t kick in until I became a campus minister at Cal State Long Beach as part of an Evangelical organization in 1980. Between 1980 and 1984, which would’ve been during the first Reagan term, the US military interventionism heated up in Central America, and the information about poverty in Africa became even more widely available. Additionally during the Reagan era was a reigniting of the nuclear arms race. As a campus minister, the two areas of activism that I became most prominently involved in were peace marches protesting nuclear weapons development and protesting military interventionism in Central America.

SK: It’s interesting to me that your initial activism took root during your role as a campus minister. It’s a departure from the traditional Evangelical campus minister role. I’m interested in how you fell into that role. Not only that, but how did you develop your own version of campus ministry, and how did your understanding of yourself in that role differ from some of the dominant ways of thinking about “Evangelical campus ministry”?

SY: The general conception of ministry of the organization I was employed by was a preoccupation with large group worship and small group Bible study. Convening and protecting students—it’s almost like congregational life. It’s about gathering people away from the evils of the university to practice Christian piety.

Fortunately, there’s another philosophy of campus ministry available that views following Jesus to mean social involvement and activism of one sort of the other. I felt like both of those approaches were legitimate, but I found the pietistic expression to be largely escapist. I do believe there are aspects of piety that are important, and I did provide those kinds of activities on occasion, but it seemed more important at the time to show that Christians shared a concern for the good society, the good life, the good person. I don’t think Christianity can be limited to the good or to the moral, but we certainly have a shared interest with other people in it. Much of my activity was trying to find collaborative ways of working on justice and peace ministry, and the denominational (including Catholic, Lutheran, Episcopalian, Methodist) campus ministers shared that vision of campus ministry more than my Evangelical colleagues tended to.

SK: We first met in a conservative Evangelical university. You have had significant interactions with Evangelicals during your professional and personal life. I know that our discussions are often critical of that tradition, but I’m curious—what do you take from that heritage that is good and that you still hold on to?

SY: One of the things that Ricoeur juxtaposes with his hermeneutics of suspicions is a hermeneutics of retrieval. And I often use the terms continuity and discontinuity: what are the things that need to be continuous, what are the things that need to be changed, shaken up.

Evangelical Christianity’s focus on a personal relationship to Jesus and it’s insistence on the individual can be challenged, and there are a number of questions that should be raised about it—but it does highlight a reality for me: the value of the human person. For all the legitimate attacks on individualism, I do think that there is an appropriate individualism that was accented in my religious upbringing that I think remains important.

I have often said that I have an irreverent piety because I embrace the full use of the English language. And I like scatological humor. Granting this caveat, emphasizing holiness and practicing a piety that isn’t judgmental towards the gutter, but is respectful of the human in all of our manifestations and dimensions is a part of Evangelical life I admire.

The politicization of Evangelicalism starting in the late 70s, and the Dobson-Falwell-Robertson version of it (the Christian radio stuff you hear)—changed the whole arrangement. I have zero interest in, a lack of respect for that version of Evangelicalism. I find it objectionable in every kind of way, and in fact I feel like practicing my impiety with some choice profanity to communicate my qualms. In a charitable mood, I recognize this approach appeals to many good people.

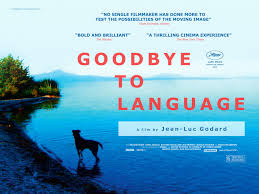

SK: There’s a whole area of your curiosity and “scavenging” as you refer to it, that we haven’t touched on, which is your love of cinema, of sights and sounds. You’ve taught film classes, founded the City of Angels Film Festival, and sat on the jury at the Berlin Film Festival. Can you comment on the role of images in our culture?

SY: Starting with the “sixties,” sights and sounds, images and music, that is to say popular culture, is the way most people experience reality and make sense of the world.

It’s no longer ideas with images being illustrative, it’s images embedded with ideas in which explanation of ideas are now the illustration. In my mind, or my eye I should say, the ocular and the auditory experiences are the power agents. We’re not going back to a logo-centric world. Ideas, books, words, and print will continue to be extremely important, but they are in the process of losing their domination. Image makers and sound designers are the agenda setters for the foreseeable future.

SK: What are some particular films that have influenced you?

SY: Taxi Driver. I really resonated with Travis Bickle, but not at a literal level. I wasn’t a Vietnam Vet with PTSD, which wasn’t in the language then, but we now know that’s what he was afflicted with. Travis Bickle saw there was something wrong with the world. He was frustrated that he couldn’t fix it. Taxi Driver, being art, uses an extreme story to try to describe how he’s going to change the moral degradation of the city of New York. But really what it ends up being is a journey into not futility, but inutility. So Travis Bickle, after all of his efforts at trying to help Iris, really discovers the limits of his ability to deal with how “f …..” up the world is—instead of lapsing into futility he recognizes inutility.

Probably why I prefer film noir, or some combination of that with crime/drama, or what we might just call gritty city films, is the extremes of the criminal world give you critical distance to see how those same dynamics operate in the suburbs or in high society. And if you have the imagination, you can see the connection points—you have to connect the dots yourself.

Art house or independent film requires a lot of effort from the viewer. For me they are really powerful spiritual experiences, and more powerful in my case than most of what we would usually think of as sacred spaces or church experiences. And this goes all the way back to the beginning of this story when I realized I was a theology and culture person. I’m looking for God in culture, and my most primal and formative religious experiences have always been in the world, in what we would call cultural locations. This is why I’ve become so interested in cultural/public intellectual life: that’s where I connect up with God.

Scott Kushigemachi is a community college English instructor. He lives in Gardena, California with his wife Amy.